Query optimization & gas

Gas is paid for any onchain query, so statement structure has an impact on cost.

There are benefits for optimizing queries in traditional databases to improve performance. But, in a web3-native database setting, this takes a whole new perspective. Since every table creation or write must go through the base chain, that means that every query is associated with a transaction and gets logged in the chain’s event logs.

In other words, every character counts since chain transactions equate to actual costs / currency. Bloated or inefficient queries mean wasted funds.

Batching queries

One consideration when making queries is how you make the call itself. When creating mutating queries, an expensive way to send these statements would be one by one—that is not optimal, assuming the following would touch the same table.

Let’s assume we have a table with schema id int, val text:

/* Some method call with a single statement */

INSERT INTO my_table (id, val) VALUES (0, 'first query');

/* A separate method call with another single statement */

INSERT INTO my_table (id, val) VALUES (1, 'second query');

It’s best to group them together into a single transaction, while also ensuring the count is under the 35kb query limit (which isn’t an issue in this example). You can combine them within a single method call when developing with any of the Tableland clients:

INSERT INTO my_table (id, val) VALUES (0, 'first query'); INSERT INTO my_table (id, message) VALUES (1, 'second query');

Considering these two write statements are inserting into the same columns, we can make this a little more efficient by collapsing them into a single INSERT statement, where the values are separated by a comma:

INSERT INTO my_table (id, message) VALUES (0, 'first query'), (1, 'second query');

Some additional ways to make this more efficient include:

- If you are inserting values into all of the columns, you do not need to specify the columns at all.

/* Before */

INSERT INTO my_table (id, message) VALUES (0, 'first query');

/* After */

INSERT INTO my_table VALUES (0, 'first query'); - For the values being inserted, consider removing spaces where possible.

/* Before */

INSERT INTO my_table VALUES (0, 'first query');

/* After, removing a single space */

INSERT INTO my_table VALUES(0,'first query');

Let’s put these all together and compare it to the original example above.

INSERT INTO my_table VALUES(0,'first query'),(1,'second query');

Note that if one of the queries in a batch fails, they all fail. This follows standard database design. Namely, upon one query failing, the database rolls back, and none of the inserts take effect. For more information, see the documentation on Tableland state.

Table & schema definition

Every character counts. If you have a write query, and the name of the table is rather long, that technically means your query is going to cost more. If you were to create a table with a prefix long_table, it has 5 more characters than one with simply table. And extending that a bit further, a table’s prefix is entirely optional, so the most efficient way to create a table is to actually drop the prefix entirely.

This detracts from human readability, though, so it’s a design consideration, potentially based on the volume of query writes. In other words, tables with a low velocity of writes aren’t impacted as significantly as one with a high volume of writes—the high volume will be repeating the table name over and over within the various SQL statements.

This is also true when defining a table’s schema. Imagine writing to a table with a column named id_column_is_super_long_and_should_be_much_shorter—this is 50 characters in total. A better way to represent this might be, simply, a column defined as id. That saves 48 characters for every write statement. Take an example schema like id int, val text. An even more cost efficient way to name these would be i int, m text.

Event logs & gas

Keep in mind there are other costs as part of standard contract calls and real-time market factors. The following is described to help demonstrate some event-level specifics since the logs are what makes the Tableland network possible. There are other factors that are incorporated in the cost, so this is more educational than showing how to calculate the total fees.

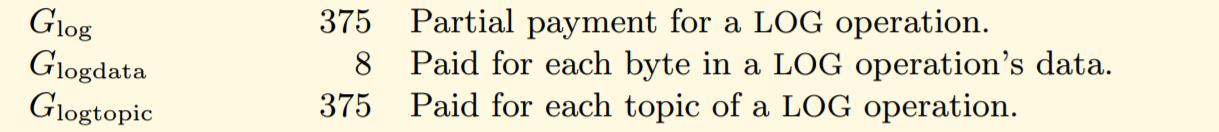

For context, let’s take a look at the cost of writing to event logs via the Ethereum yellow paper, which is what all EVM chains implement:

Every log has topics and data. A topic is a way to "easily" search for a specific identifier in the event logs since it’s indexed. First, a quick technical overview:

The maximum number of topics for an event is 4 total, which typically includes the function signature and each indexed variable. A "maxed out" number of topics for event looks something like the following, where

indexedmakes the data itself searchable in the event logs. Thus, variablesa,b, andcare topics, along with the function signature itself—this adds up to 4 total topics. The remainingdandeare simply just data (unindexed) as part of the event logs.

event MyEvent(uint indexed a, uint indexed b, uint indexed c, uint d, uint e);

When calculating how much event logs cost, one must consider the cumulative total where there is a base gas fee of 375, plus 375 gas per topic, plus the actual size of the data where each character is 8 gas. There’s also some "memory expansion" that must be considered but is ignored for simplicity sake.

Note that Tableland doesn’t use the indexed keyword in the registry smart contract’s events, so the number of topics is one. Namely, whenever a table is created or written to, one indexed parameter is emitted.

Each byte—or character in a query string—costs 8 gas. A statement that has a table name with 50 characters vs. one with 1 character means there is a difference of 49 characters, or 392 gas. Multiply that by the frequency of mutating SQL statements and the potential inefficiencies outline above, and query costs can add up to more than they need to.

As a comparison, writing to storage costs 20,000 gas per 32 bytes. This is the reason why Tableland can create huge cost savings as an alternative to or a projection of smart contract storage. And even when writing to the event logs, the aforementioned considerations can help eliminate unneeded bytes that attribute to computational gas fees.